Before the legend, there was a boy, a lake, and a version of himself he never stopped chasing.

I fell in love with Ernest Hemingway the way most English Lit majors do—somewhere between a battered copy of In Our Time and the long, quiet ache of The Sun Also Rises during my studies at the University of Hawai‘i. Imagine that. A Michigan girl who couldn’t wait to break free finds a bond back home through the literature of another—and 5,000 miles away from home.

It wasn’t the machismo that drew me in. By my early 20s, I’d already had enough of the male bravado. It wasn’t the bullfights or the bourbon or the war medals—though they all add to a life lived on the edge. It was the struggle. The emotional violence just beneath the surface. The discipline of a man who couldn’t always say how he felt, so he cut his sentences down until only the pain remained. That kind of writing only comes from someone who’s been chewed up by life and still—somehow—keeps showing up to the page.

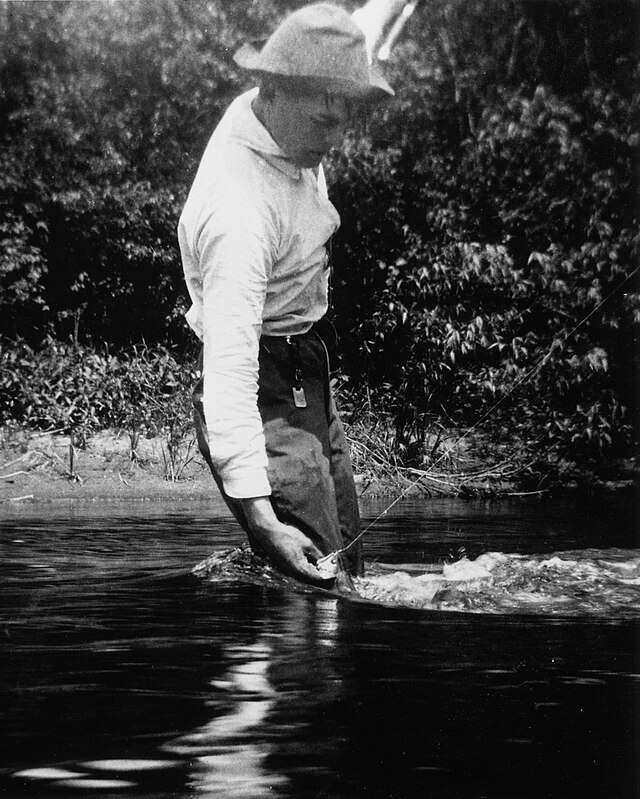

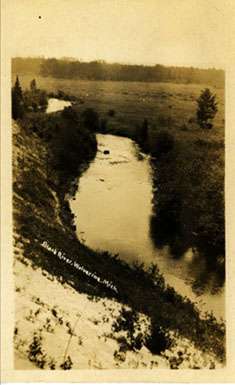

What most people don’t realize is that before the wars, before the Nobel, before the public unraveling, Hemingway belonged to the Great Lakes. He was born here, in Oak Park, Illinois, part of the watershed. He spent his earliest summers in northern Michigan—fishing its lakes and rivers, walking the dirt roads of Horton Bay, nursing heartbreak along Walloon Lake. The Hemingway myth starts in Paris. But the man? He began here. And maybe, in a sense, he ended here too.

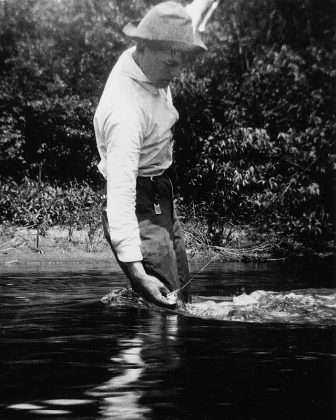

Michigan taught him to hunt and fish, yes. But it also gave him something far more dangerous for a man like Hemingway: stillness. In the woods and on the water, there were no expectations, no medals to earn, no personas to uphold. He could simply be Ernest.

For a boy raised in a place he is later said to have describe as having “wide lawns and narrow minds,” the wildness of Michigan was not just a landscape—it was freedom. It was where he learned that masculinity doesn’t have to mean bravado. It can mean silence. Tenderness. Reflection. Even grief.

That tension—between toughness and tenderness—is all over his early work. And it’s all over this region too. It’s hard not to feel it if you grew up in small-town Michigan, where men still struggle to say how they feel, where quiet suffering is often mistaken for strength. Hemingway knew that mask intimately. But in the north woods, I think he could take it off, at least for a while.

He wrote about the war, but he also wrote about Seney. He wrote about Paris, but not before he wrote about a quiet boy named Nick Adams—wandering, wounded, and alone in the woods of northern Michigan. The Nick Adams stories weren’t fiction. They were Hemingway—stripped down to his rawest self. Michigan wasn’t a backdrop. It was a mirror.

In Big Two-Hearted River, Nick Adams returns from war not to talk, but to fish. To pitch a tent. To try and breathe. There’s no mention of what happened overseas, no exposition, no catharsis—just a man in a forest, trying to feel something again. That story is more than a literary exercise in minimalism. It’s a survival manual for a man with too many ghosts and no place to put them. Hemingway didn’t imagine that scene. He lived it. After being wounded in World War I, he returned to Michigan to recover. He went north. Always north. Back to the rivers, back to the silence.

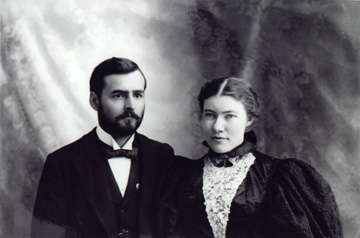

And there were real stories, too—ones that never made it into the books. Hemingway caught trout near Horton Bay with his father, a man both admired and feared. He danced with his first love, Marjorie Bump, at the Red Fox Inn. He never proposed as he expected, but he did immortalize her heartbreak in a short story called The End of Something—set against the same waters where they once swooned. And he struggled with the emotional aftermath of the break up in The Three-Day Blow. Imagine the pain of seeing your life—your heartbreak—immortalized in print. Forever. A few years later, he returned to those same northern shores—not for Marjorie, but to marry his first wife, Hadley Richardson, in a quiet ceremony in Horton Bay in 1921. Michigan didn’t just give Hemingway stories. It gave him consequences. It gave him women who walked away. It gave him reflection.

He returned again in 1947, long after his fame had calcified. He was heavier by then—physically, emotionally. He stayed in Walloon Lake, reportedly distant, quieter than usual. Some say he was chasing ghosts. Others say he was trying to outrun them. But even in that version of himself, he still came back. Still walked those woods. Still cast lines into those same rivers.

It’s easy to talk about Hemingway the caricature: the drinker, the womanizer, the war chaser. It’s also easy to hate that version of him. But there’s another Hemingway—the one who cried after putting down animals, who once sat for hours at the edge of a lake trying to name what he felt. Michigan knew that Hemingway. Intimately.

He wasn’t perfect, but he was real. And he was ours. And maybe that’s what keeps calling me back. Not his strength but his silence. Because I’ve loved men like that. And I’ve carried that kind of ache myself—with nowhere to put it.

Hemingway may have met death on his own terms in Ketchum, Idaho, but he never really left northern Michigan. It held his peace, and his pain. His beginnings, and maybe even the version of himself he wished he could return to. That’s the Hemingway I’ll never stop loving. Not because he was strong. But because he was fragile, and didn’t know where to put it.

Michigan-Set Works by Hemingway

You can read The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, including those set in Michigan through the non-profit library, Internet Archives. It’s free.

Big Two-Hearted River (Parts 1 & II); Setting: Seney, Michigan

The End of Something; Setting: Horton Bay, Michigan (Read Story with The Three Day Blow excerpt here)

The Three Day Blow; Setting: Bill’s Cottage near Petoskey (includes Nick’s emotional response to break up with Marjorie over drinks, denial, and inner turmoil.)

Up in Michigan; Setting: Horton Bay, Michigan

Indian Camp; Setting: Lake region near Walloon Lake

The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife; Setting: Walloon Lake/Windemere Cottage area

Ten Indians; Setting: Fourth of July in Petoskey region

The Battler; Northern Michigan woods and towns

The Light of the World; Setting: Northern Michigan woods and towns

The Last Good Country; Setting: Northern Michigan woods and towns

The Torrents of Spring (1926); Setting: Petoskey, Michigan (satirical novella)

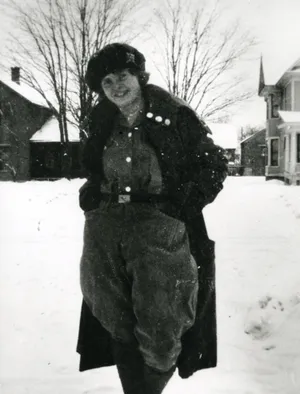

The below images are sourced via Central Michigan University, Wikimedia Commons and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.