THE DISAPPEARANCE AND DISCOVERY OF THE IRONTON IN THE WATERS OF LAKE HURON

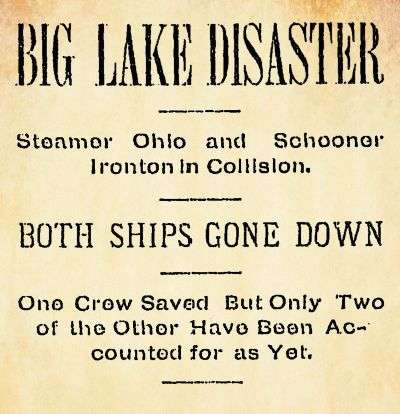

In the late hours of September 26, 1894, in the ominous depths of what is known as “Shipwreck Alley” the steamer Ironton, a vessel seasoned by the waves, met with catastrophe—a disaster that would claim five lives and etch another somber tale into the maritime history of the Great Lakes.

The Irontone’s journey on this night began like many others. The 190-foot steamer Charles J. Kershaw had embarked from Ashtabula, Ohio, with two schooner barges (unpowered vessels), Ironton and Moonlight, in tow, their hulls empty and echoing, bound for Marquette on the shores of Lake Superior.

Fate had other plans.

We struck her on the quarter, aft of the boilder house. a light was lowered, and we saw a hole torn in our port bow, our stem shattered.

William Wooley, Surviving Crew Member

At the stroke of 12:30 a.m., as they sailed atop the waters of Lake Huron, disaster struck. The Kershaw’s engine sputtered and failed, leaving it powerless under the night sky and leaving the schooners Ironton and Moonlight at the mercy of the Lake.

Adrift and at the whim of a growing south wind, Ironton and Moonlight loomed ominously close to the disabled Kershaw.

In a frantic bid to avoid a disastrous entanglement, the crew of Moonlight made a critical decision—they cut Ironton’s tow line, the waves pushing her into the vast darkness.

Captain Peter Girard of the Ironton, seasoned yet suddenly powerless, worked feverishly with his crew to maneuver their rogue vessel. They managed to fire up an auxiliary steam engine and unfurled the sails in a desperate attempt to regain control. But their efforts were in vain.

The Ironton, caught by the wind, was thrust directly into the path of the Ohio—a 203-foot wooden freighter laden with 1,000 tons of grain, bound for New York from Minnesota.

The collision was both sudden and devastating. The Ohio’s sturdy hull collided with Ironton, causing a catastrophic tear.

William Wooley, a crew member of Ironton and one of the two survivors, recounted the chaos in a haunting interview with the Duluth News Tribune the following day, “We struck her on the quarter, aft of the boiler house. A light was lowered, and we saw a hole torn in our port bow, our stem shattered.”

As both vessels reeled from the impact, Ironton’s crew scrambled to abandon ship. The sea, unforgiving and relentless, claimed the vessel quickly after they launched their lifeboat.

But in the panic, a fatal mistake was made—the lifeboat was not detached from the sinking ship. Trapped by the painter, the lifeboat was dragged down with the Ironton, leaving its crew to fight for survival in the cold waters.

William Parry, another survivor, narrated his terrifying ordeal to Duluth News Tribune: “As the Ironton sank, it took the yawl with it. I went under, coming up only to grab a sailor’s bag. Wooley was nearby, floating on a box.”

Their ordeal ended hours later when the steamer Charles Hebard, passing by, noticed the desperate men and rescued them from the clutches of the cold lake. The other members of the crew, including the brave Captain Girard, were not so fortunate, swallowed by the depths of Lake Huron.

The Ironton remained lost beneath the waves, a silent relic hidden from sight and memory for over a century, until its rediscovery transformed it from a mere footnote in maritime history to a captivating chapter of the Great Lakes’ shipwreck legacy.

For over 100 years, the final resting place of the Ironton was shrouded in mystery. It wasn’t until advances in underwater technology and the relentless pursuit of historians and wreck hunters that the pieces of the puzzle began to align.

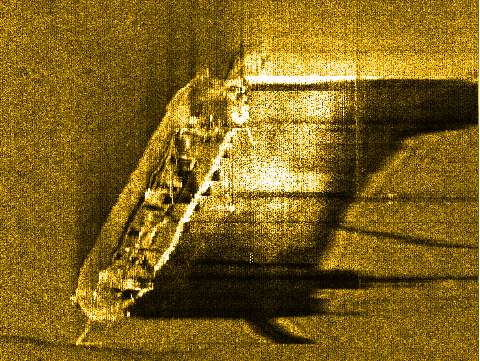

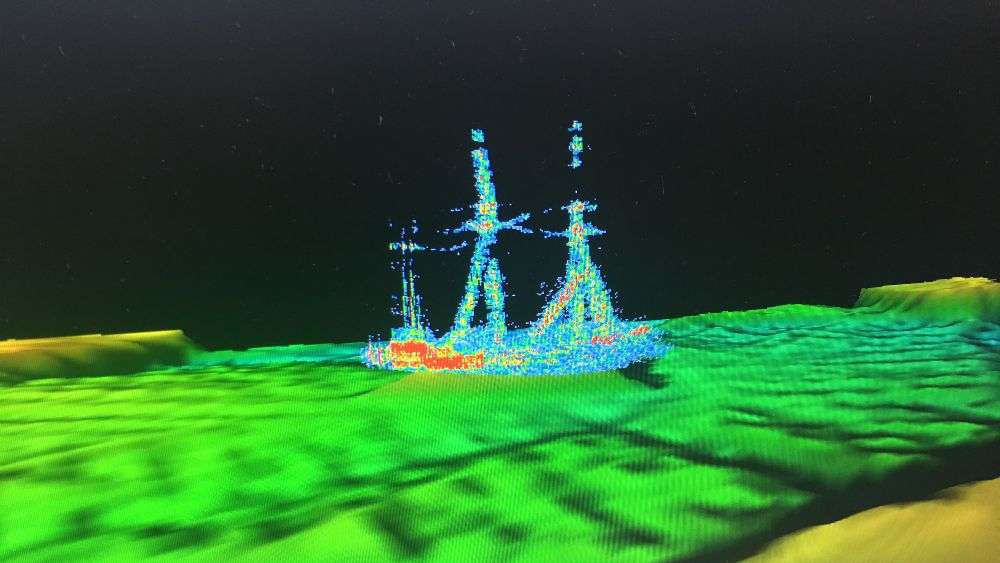

The breakthrough came when a team equipped with sophisticated sonar and diving equipment pinpointed the Ironton nearly 120 years after its tragic sinking.

Resting solemnly over 320 feet below the surface, the Ironton was found remarkably intact, a snapshot of a bygone era preserved in the lake’s icy waters. The ship lay a few miles offshore, northeast of the Presque Isle Lighthouse, which once served as the beacon of safety for the ships victim to this very wreck.

The discovery was not just significant in piecing together the historical narrative; it was a technical marvel, achieved through the efforts of both seasoned divers and historians who meticulously mapped the coordinates and underwater currents of Shipwreck Alley.

As the Ironton sank, it took the yawl with it. i went under, coming up only to grab a sailor’s bag. wooley was nearby, floating on a box.

William Perry, Surviving Crew Member

The exact location of the wreck, relative to the lighthouse and the shoreline, provided crucial data for understanding the dynamics of the ship’s final moments and the brutal forces of nature that led to its demise.

Moreover, the site of the wreck offered a rare glimpse into the construction and operation of schooner barges of the late 19th century. Divers documented the Ironton’s features: from the wooden beams braced for heavy loads to its cargo hold, which once carried vast amounts of grain and coal across the Great Lakes.

The rediscovery of the Ironton has since attracted historians, explorers, and maritime enthusiasts, eager to connect with the past and to honor the memories of those lost at sea.

Each dive to the wreck not only brings back stories long submerged but also serves as a solemn reminder of the perilous beauty and unforgiving nature of the Great Lakes.

The Ironton, now a poignant underwater museum, continues to teach and remind us of the mighty challenges faced by those who once navigated these inland seas.

The Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, located in Lake Huron off the coast of Alpena, Michigan, is a haven for maritime history enthusiasts and underwater explorers. Spanning 4,300 square miles, it protects one of America’s best-preserved collections of shipwrecks, with over 100 discovered and many more believed to lie within its waters. These submerged relics, dating back to the 19th century, offer a captivating glimpse into the Great Lakes’ rich nautical past. The sanctuary not only preserves these historical treasures but also provides opportunities for research, education and recreation, making it a premier destination for diving, boating and learning about maritime heritage. Fore more information, visit the sanctuary website.