Carved by Time. Painted by Nature.

Stand on the edge of Lake Superior and you’re standing at the edge of time. Where water carves memory into stone. The water stretches out like an inland ocean (they behave like inland seas, but aren’t technically), a thousand shades of blue and green shifting with the wind. Towering above that seemingly endless water are cliffs splashed in streaks of burnt orange, moss green, ochre, and white. Natural murals painted by minerals seeping through the stone.

This is Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, one of the most breathtaking places in the Great Lakes Basin and, without exaggeration, one of the most unique geological wonders in the world. But those cliffs didn’t just happen overnight.

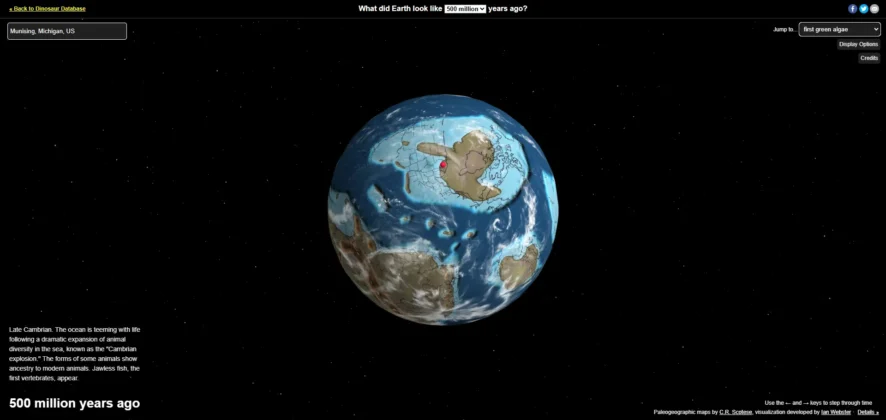

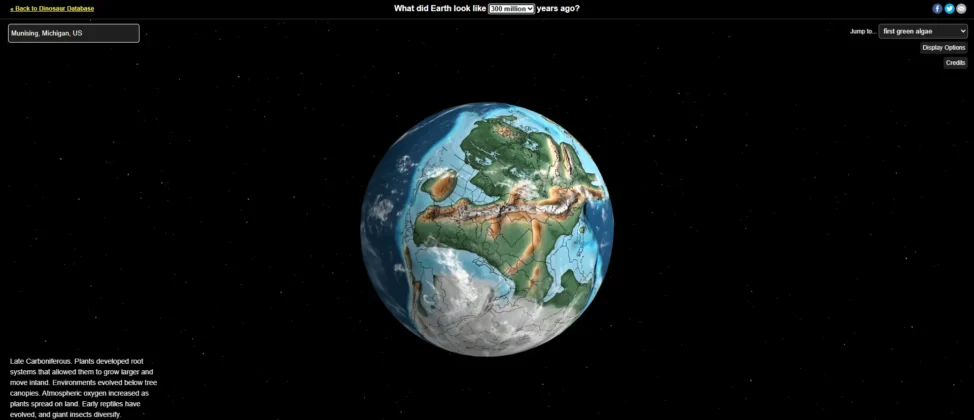

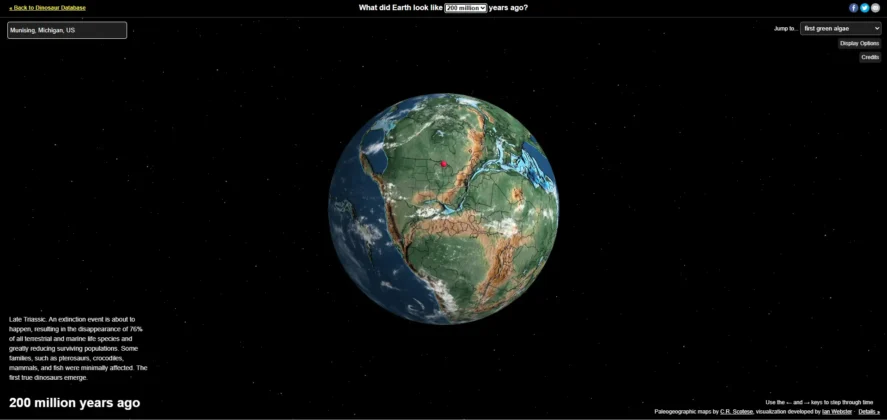

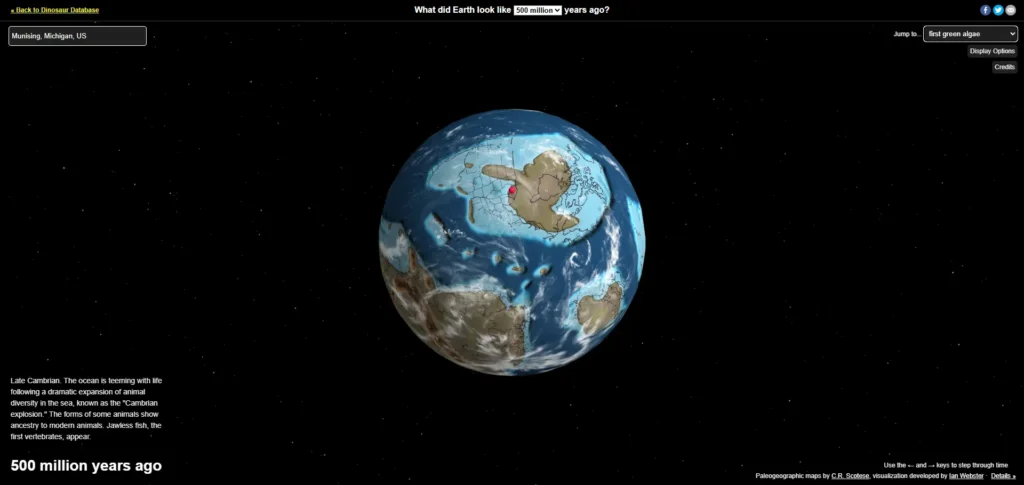

They are the product of nearly 500 million years of slow, steady transformation and tectonic shifts that moved the earth.

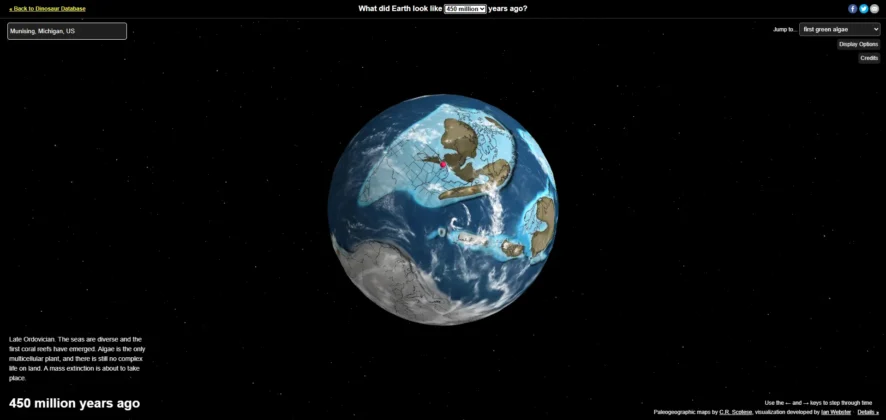

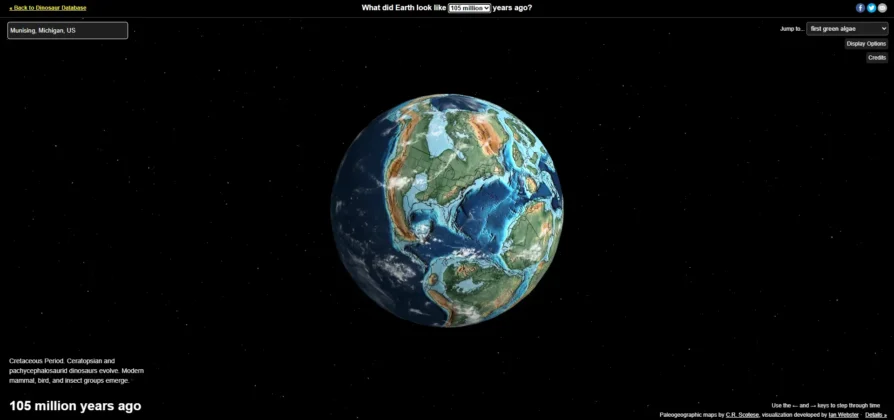

To understand Pictured Rocks, you have to start at the bottom of the sandstone cliffs themselves. These cliffs are part of the Munising Formation, ancient deposits of sand, mud, and minerals laid down more than 450 million years ago, when the land that would one day become Michigan was located much closer to the equator.

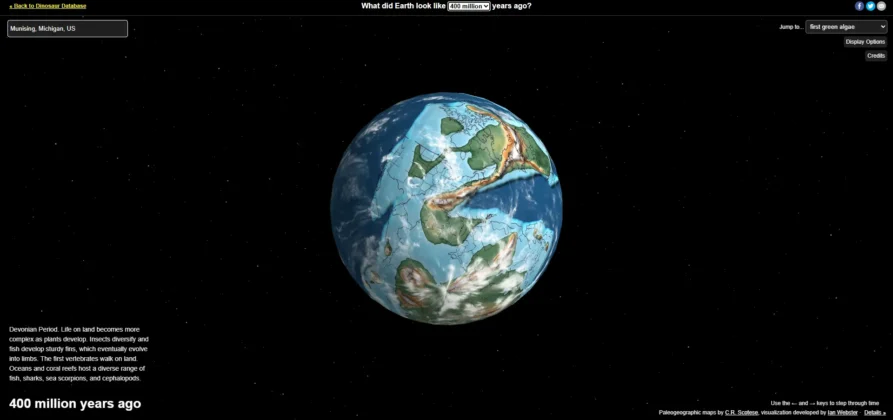

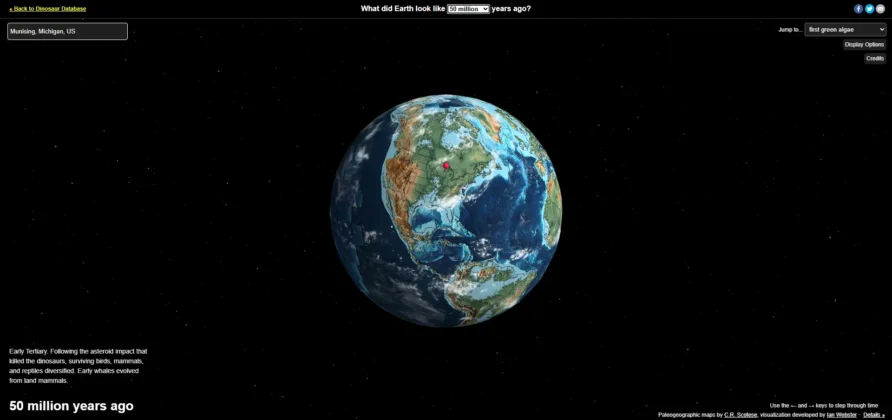

Back then, the continents were still drifting into place. Through the slow movement of tectonic plates, this region was positioned in a tropical zone and submerged beneath warm, shallow seas teeming with marine life.

Layer by layer, sediment settled onto the seafloor—sand, silt, and minerals that would eventually be compacted and cemented into the stone we see today. Over hundreds of millions of years, this landmass drifted. As its position changed, so did the climate—shifting from tropical to temperate, and eventually to the colder conditions we know today.

The remains of those ancient seas are still written in the land. Michigan’s sandstone cliffs, inland salt beds, and fossil records all trace back to this tropical past. Fossils of coral reefs, trilobites, and other marine life can still be found across the state. A reminder that this place was once part of a thriving oceanic world.

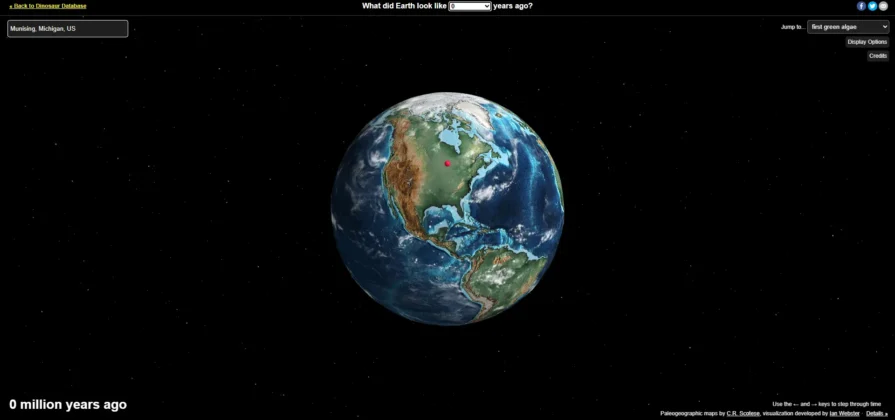

And though this land was once part of a tropical sea, it’s the cold, relentless waves of Lake Superior that shape it now.

Today, Lake Superior holds 10% of the world’s fresh surface water—and the Great Lakes together hold about 21%. They hold about 84% of North America’s fresh water. Its waves, driven by winds that can sweep across hundreds of miles, hammer the shoreline constantly. Over time, they chisel caves and arches into the cliffs, and as those arches fall, the shoreline reshapes itself—inch by inch, year by year.

What’s left behind is a mesmerizing landscape of towering walls, hidden grottos, and jagged stacks of rock that look as if they belong in another world.

If the shapes of the cliffs are incredible, their colors are otherworldly. The “pictures” that give Pictured Rocks its name are painted by mineral-rich groundwater trickling down the stone.

- Iron leaves red and orange streaks.

- Copper leaves blues and greens.

- Manganese creates black.

- Calcium forms white streaks like dripping paint.

The result? A natural gallery stretching 42 miles along Lake Superior—where every cliff face tells a story millions of years in the making.

Long before it was a national lakeshore, Pictured Rocks was part of the homelands of the Anishinaabe people, including the Ojibwe, who have lived along Lake Superior for thousands of years and call it Gichigami, meaning “Great Sea.” While the name “Pictured Rocks” refers to mineral-stained cliffs rather than rock art, the shoreline remains a living part of Anishinaabe history and culture.

Across the Lake Superior basin—at places like Agawa Rock in Ontario—pictographs created by Anishinaabe ancestors still tell stories of creation, spirits, and the deep connection between people and water. These images, some fading with time, are reminders that this landscape is not just beautiful, but also spiritual, alive, and part of a living history that stretches far beyond the park’s boundaries.

When Congress created Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in 1966—the first national lakeshore in the country—it was in response to growing concerns about development and logging along Lake Superior. Protecting this stretch of shoreline wasn’t just about saving its beauty; it was about preserving an irreplaceable ecosystem.

Today, Pictured Rocks receives more than 800,000 visitors every year. Many come by kayak, paddling beneath the cliffs to float into caves and get an up-close look at her painted beauty. Others take boat tours or hike along the North Country Trail that weaves through forest and along her cliff edges.

But with so much visitation comes the need for preservation. Lake Superior’s storms are powerful, and its water is cold and unpredictable. Erosion is a constant threat, accelerated by climate change. Some iconic formations—like the turret at Miner’s Castle—have already collapsed. During one of my visits, a small section of a cliff side cracked and plunged into the waters below. There are several points along her shoreline where you can see the remains of fallen sections of rock.

And as more people come to experience her beauty, there’s a growing need for responsible tourism. Staying on marked trails, respecting the water, and honoring the cultural heritage of the area isn’t just good practice, it’s essential for keeping this landscape intact for future generations.

Because when you’re Standing on the cliffs at Pictured Rocks, you feel something bigger than yourself. You feel how small and fleeting human time is compared to the slow work of wind and water. You feel how easily something so ancient can be lost.

This is why Pictured Rocks matters. Not just because it’s beautiful, but because it connects us—to the Earth, to history, to each other.

And it’s why we must protect it.

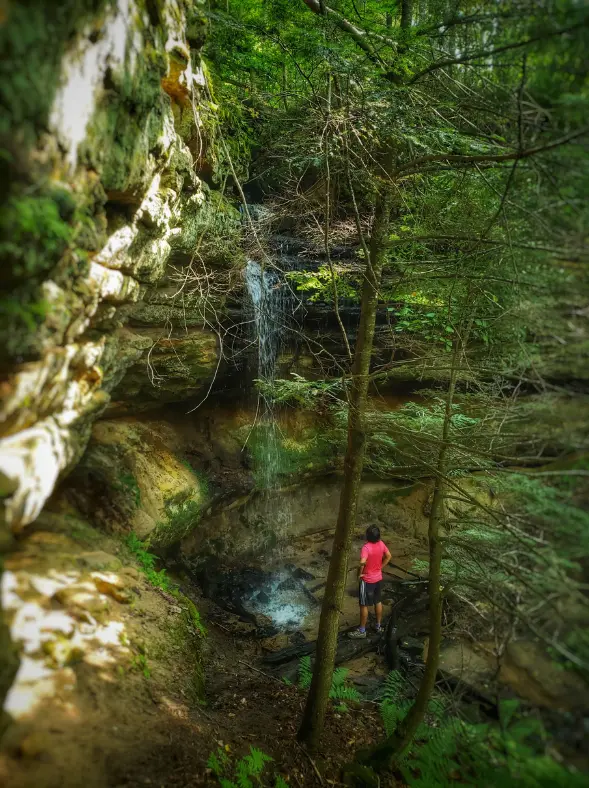

I’ve been to Pictured Rocks many times, and every single visit feels like the first. It’s one of my favorite places in Michigan. I especially love the formations and colors of Battleship Row. The Chape Cove, the Chapel Falls, it’s all so stunning and rich in color, beauty, and history. Each trip reveals something new—a different angle of light on the cliffs, a cave I hadn’t noticed before, a moment of stillness on the water that anchors me where I’m at.

I’ve captured incredible photos and video over the years—many of which you will find on this page—but none of it truly does this place justice. You have to experience it, right along with the feel of the cold spray of Lake Superior on your face, and hear the echo of waves through the arches to truly understand its power.

That’s why I’ll keep going back—and why I’ll keep sharing the stories, images, and videos that remind us what’s at stake.

If you’ve been to Pictured Rocks, I’d love to know: what’s your favorite spot? Did you paddle beneath the arches? Hike the trails? Watch a Superior sunset from the cliffs?

Because the more we speak about what we love—what we’ve stood beside, hiked through, paddled under—the better our chances of preserving them. Not just as pretty photos on social media, but as living landscapes that tell the story of who we are and where we come from.

Tag us in your posts @greatlakespulse.

Help us defend and preserve nature. Click the Shop the Drop below and help us fund our efforts. You can also visit our foundation website to provide a donate to our Great Lakes Basin Initiative, and learn how you can help.