November is federally recognized as Indigenous Peoples’ Month in the United States – a time that we are to recognize the Native peoples of our land and celebrate the culture, traditions, and customs of their communities. I find this all a bit disingenuous. True recognition of Native peoples requires more than a single month of acknowledgment. It demands ongoing reflection, reconciliation, and action.

Nowhere within this “celebration” do we discuss – out loud – the reconciliation and healing of our Native brothers and sisters for their indescribable sacrifices – both provided and forced – made to shape the western development of the land they have called home for centuries and we have called home for a mere 247 years.

A few of our national leaders make a postured speech or two, but there is a stark absence of genuine conversation or action outside of the Indigenous community regarding reconciliation and healing of centuries of trauma. I see a multitude of tribes – all sovereign nations within our nation – who continue to struggle to be recognized and heard.

Throughout last summer, I worked to connect with several of the 12 federally recognized tribes that call Michigan home. Ironically, this past November (during Indigenous Peoples’ Month), I started receiving responses after months of trying. I had little knowledge of the world in which I was about to enter. Reading recorded history does not even begin to scratch the surface of the truths that are starting to emerge.

If the historical record paints a grim picture of these institutions, the true weight of their impact emerges through the voices of survivors. These initial connections have led me to The Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs and several of its survivors.

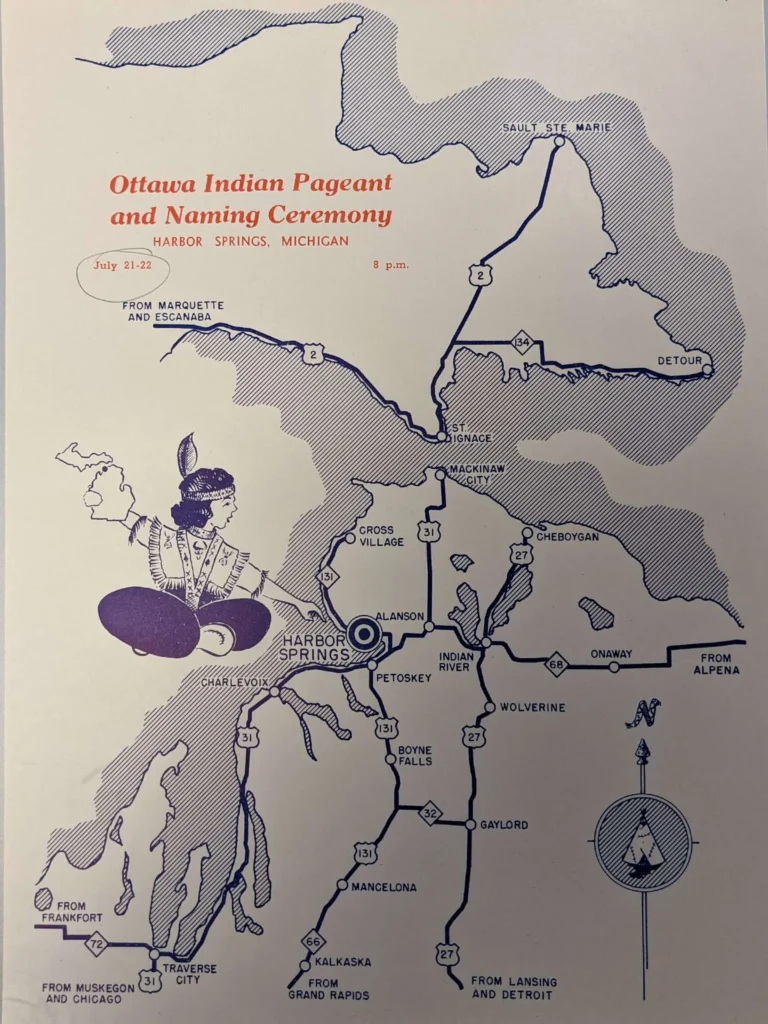

Harbor Springs is a beautiful, picturesque town on the north-western shores of the upper lower peninsula on Lake Michigan. If you’ve never been, you should visit. It is home to ski resorts, hiking trails, quaint shops, and some lovely people I personally know. The area in and around Harbor Springs is one of my favorite places in Michigan. It’s also home to one of the 12 federally recognized tribes of Michigan – The Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

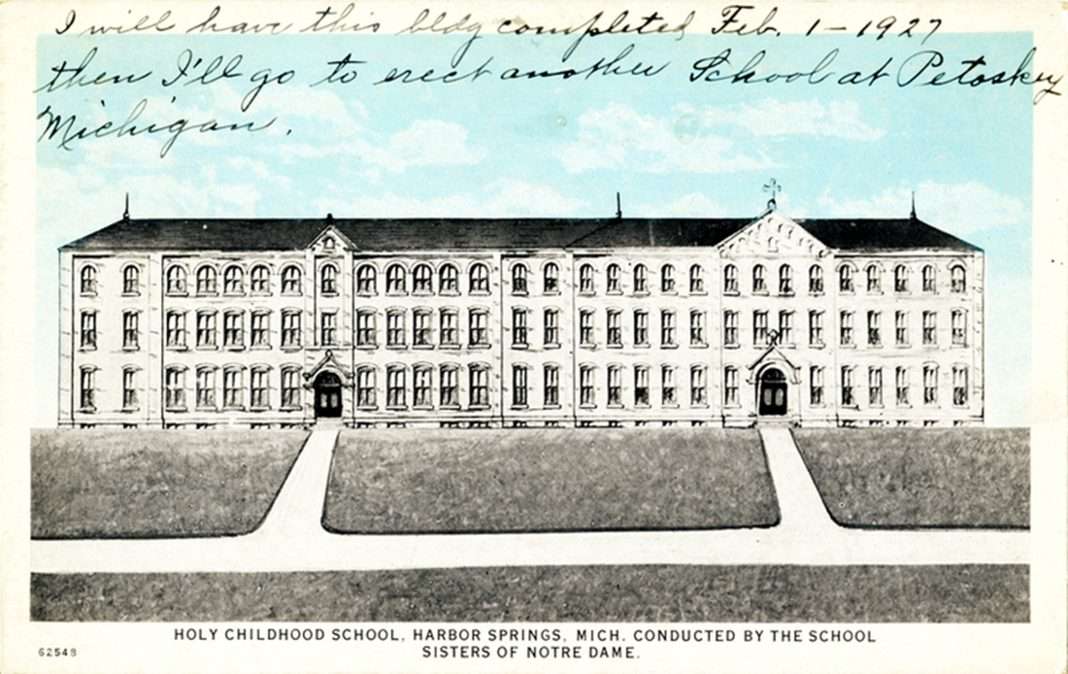

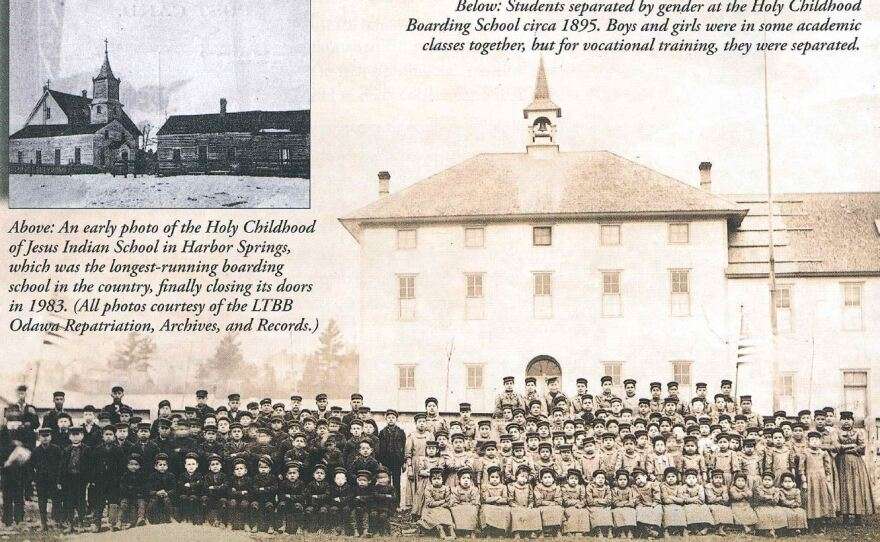

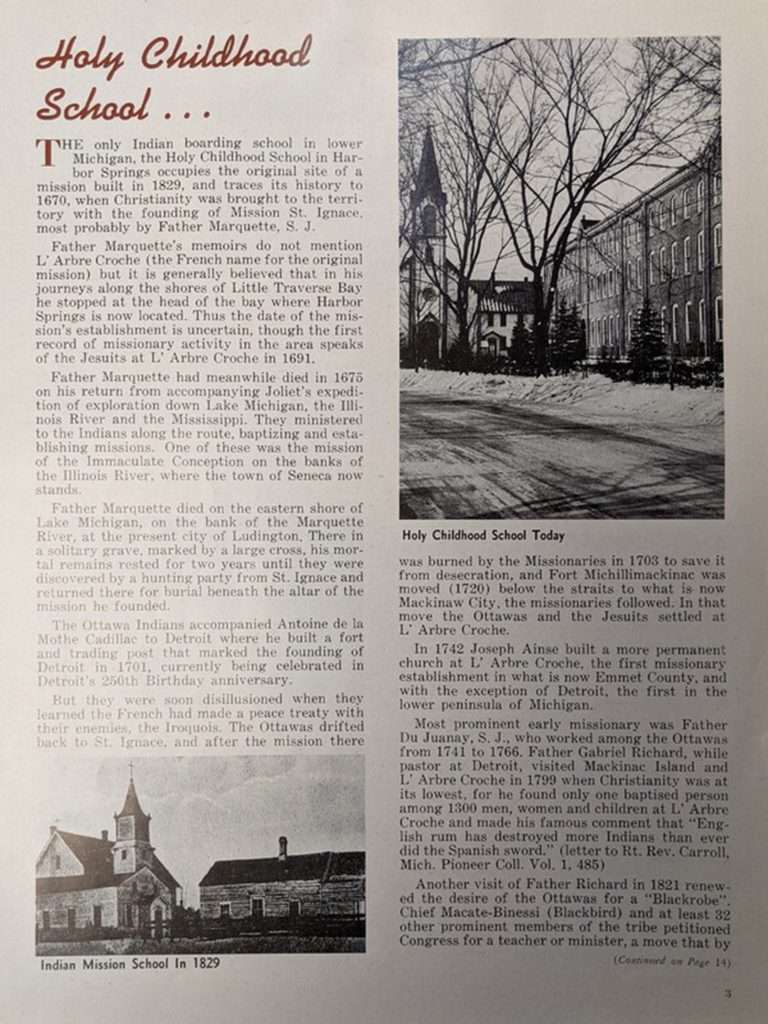

This beautiful little town is part of a dark chapter in our history, and one we must acknowledge. It was the home of The Holy Childhood School of Jesus operational from the 1880’s to 1984. It was the first federally funded Indigenous boarding school in Michigan, though it was the second boarding school in Harbor Springs. The first boarding school was named New L’Arbe Croche and opened in 1929. This French-mission school was built in 1829 with the help of the Odawa tribes in the area and taught lessons in Anishinaabemowin. It lasted only a few short years.

In the 1880s, The Holy Childhood Boarding School – run by The Sisters of Notre Dame (even with federal funding) – opened its doors with federal support to “assimilate” Indians into white, Christian culture based on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School model, the first Indigenous boarding school in the United States. Authorized by Congress, Carlisle opened in 1879 in Philadelphia and operated for 30 years. The school’s first superintendent, Captain Henry Pratt, chose an abandoned army barracks as the school building and advocated for the “Americanization” and cultural assimilation of the Indians.

The purpose of assimilation?

“Kill the Indian and save the man.”

“Kill the Indian” is exactly what they attempted to do. And sometimes they succeeded – literally and figuratively.

The assimilation efforts of our Native peoples trace back to 1790 and driven by early American leaders George Washington and Henry Knox, the United States Secretary of War, Revolutionary War general, and founding father. They believed that cultural erasure was the key to unity. Boarding schools became the centerpiece of these efforts. Education, they believed, was the most effective tool for acculturating Native peoples into white, Christian society.

The belief was that if Native peoples were to learn the customs and values of white United States, they would be able to merge tribal traditions with white American culture and “peacefully” unite society.

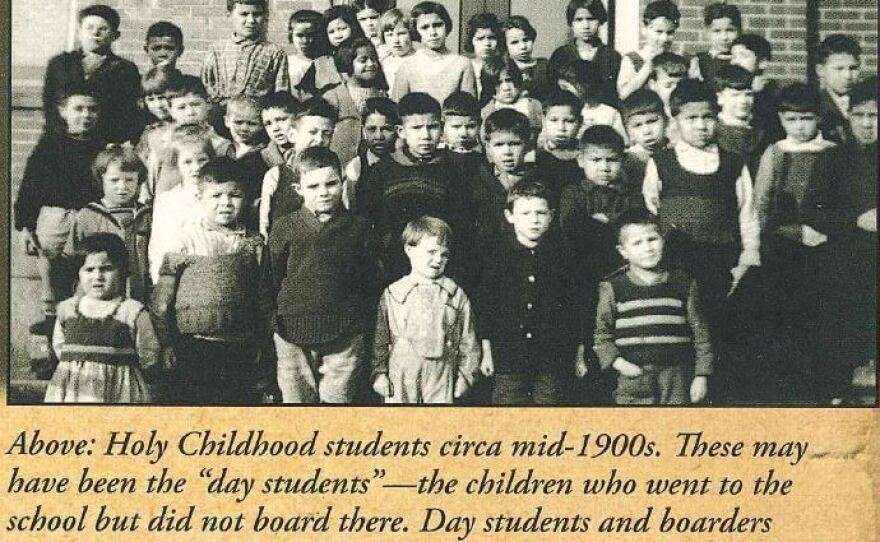

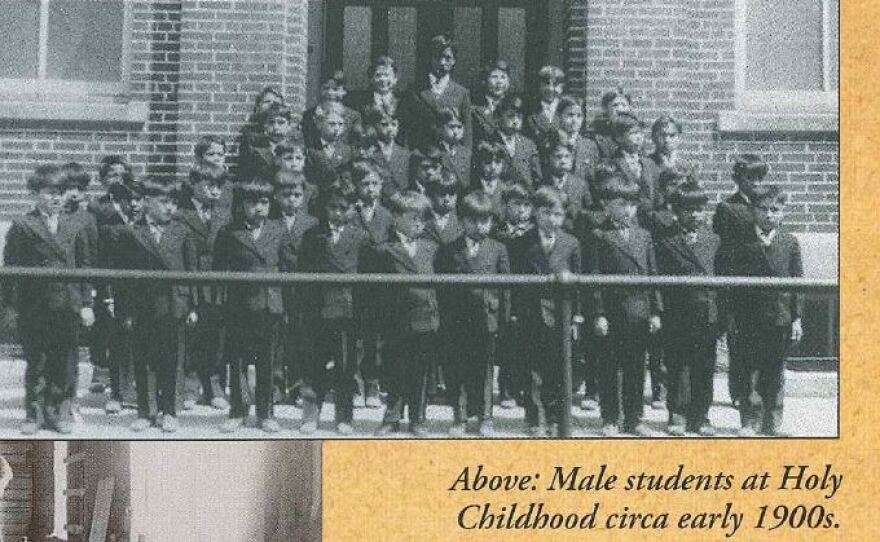

Post-Indian Wars, the federal government effectively banned the practice of traditional Indigenous religious ceremonies (so much for freedom of religion). From there, it established the Native American boarding schools, where Native children were mandated to attend. Children were taken from their families at very young ages – often by force – and placed into these schools; some only saw their families once per year, others not for years, many never again.

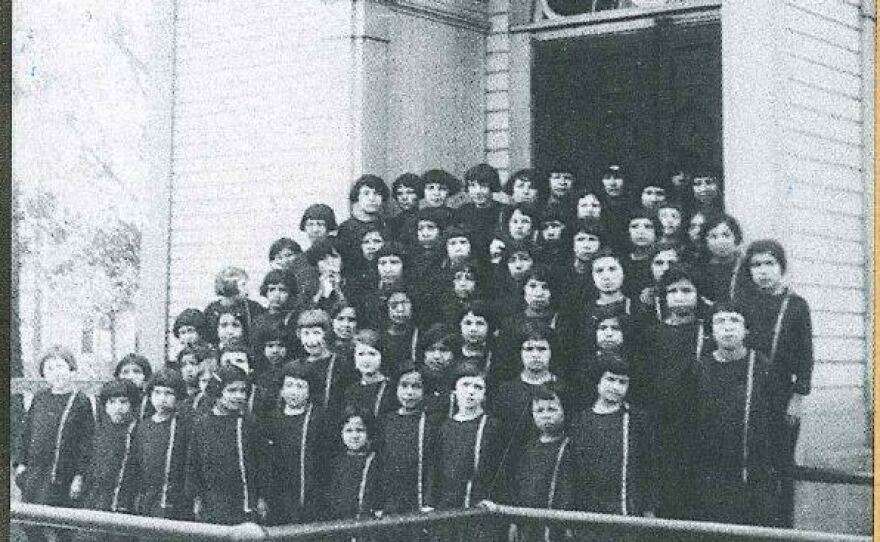

The profound truths emerging from survivors of these schools reveal a history of abuse – physical, verbal, mental, and sexual. They were forced to speak English, study standard subjects, attend church, and have their tribal traditions erased. I learned through the personal conversations with surivors that the traumatic experience began with the symbolic act of cutting off their long hair, which holds spiritual significance in the Native culture. The boys were given short cuts and the girls were given pageboy cuts. It is believed in Native culture that long hair holds knowledge wisdom, power, and resiliency. Cutting the hair was the first step toward “killing the Indian.”

The truths we are about to hear through the words of survivors of Holy Childhood are difficult to hear, but we must listen and hear them. They are descriptions of abuse and torment. They include conversations about those who are lost to this day in unmarked burial grounds, and as I have recently learned – knowingly beneath a paved road in Harbor Springs.

These stories are not just history—they are a call to action. As we listen to survivors of the Holy Childhood School of Jesus, we must commit to amplifying their voices, supporting their healing journeys, and addressing the systemic challenges that perpetuate generational trauma.

Those of us who are ancestors of this white assimilation must pause and not make this reconciliation and healing process about us. It’s not about “white guilt” or “apologizing for being white” that so many jump into. It’s about acknowledging the atrocities that our Native peoples went through at the hands of our ancestors. It’s about hearing their truths. It’s about reconciling the past and helping them heal their generational trauma. It requires a commitment to truth, understanding, and empathy.

It is incumbent upon us to engage in open dialogue, amplify Indigenous voices, and support initiatives that address the systemic challenges perpetuating their trauma. By coming together and respecting the autonomy and resilience of Indigenous communities, we can contribute to a collective journey towards reconciliation, and foster a future of healing and cultural revival – all central tenets of our shared national narrative.

In the coming months and beyond, you will read and hear the many truths and conversations directly from survivors of The Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. These are their words, not mine. Through podcasts and the written word, we will share and amplify their voices, and their truths, and walk beside them through their healing journey into a shared, unified future.

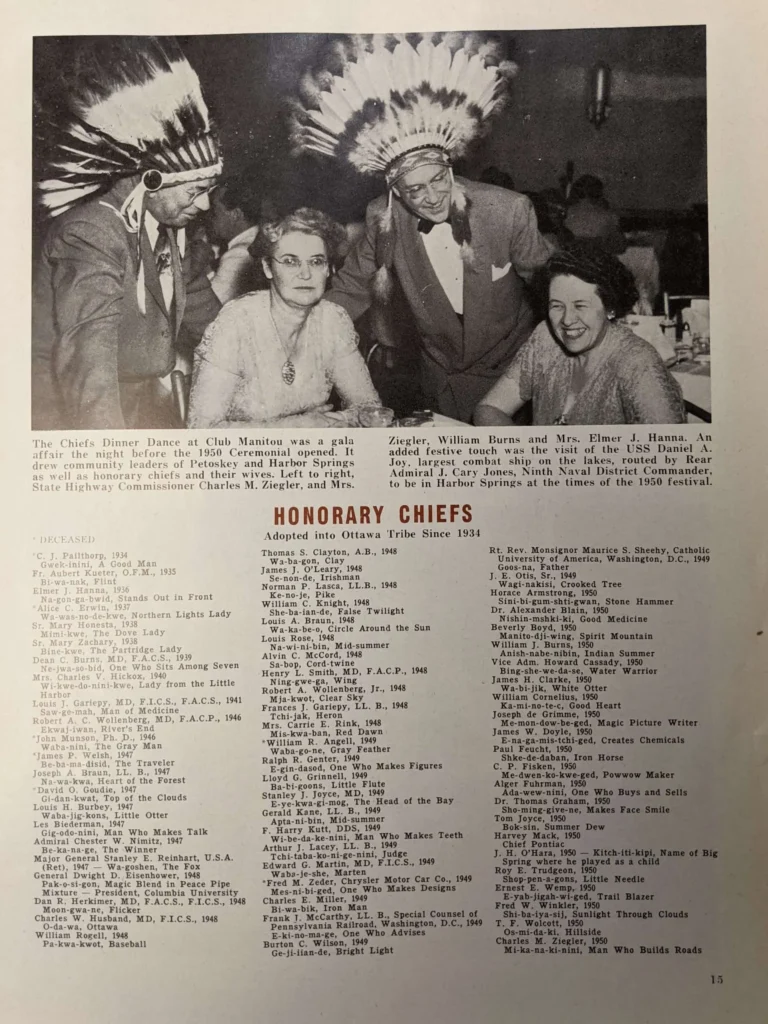

The Michigan Indian Foundation, Inc. was a private organization made up of wealthy white Michiganders who financially supported The Holy Childhood School of Jesus. The images on these pages are from their Annual Review from 1949-1950 and the language they used to appeal to donors.

Additionally, their annual “Naming Ceremony” common throughout the 1950s was a gala that named “Honorary Chiefs” to the Odawa tribe and was used to recruit potential donors to the school. It provided an economic boost to the area and was used to promote the lie that the nuns “lovingly devote themselves to the care of Indian children.”

Acknowledging these truths is a necessary step toward reconciliation and healing. By amplifying Indigenous voices, engaging in open dialogue, and supporting their healing journeys, we can help build a future rooted in understanding, empathy, and respect.

Listen to our Podcast Series Reconciliation and Healing of Michigan’s Indigenous Peoples with Survivors of the Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. Read the related articles of this series, A Native American Woman’s Journey from Childhood Trauma to Survivor and Truth Teller.

Watch for our documentary Indigenous Voices coming in 2025. To help support the production of this documentary, please visit our foundation website lovewhereyoulivefoundation.org. We will soon have products for sale that will also help raise funds for this project and to support our Native brothers and sisters on their journey toward reconciliation and healing. Check back soon!

All image sources: Bently Historical Library, University of Michigan